Home / Mumbai / Mumbai News / Article /

Mumbai: Bandra resident on a hunger strike for faster court hearings

Updated On: 16 February, 2022 08:45 AM IST | Mumbai | Hemal Ashar

Anil Gidwani, 63, believes protest to highlight delays within judicial system and call for change worth his weakness, discomfort

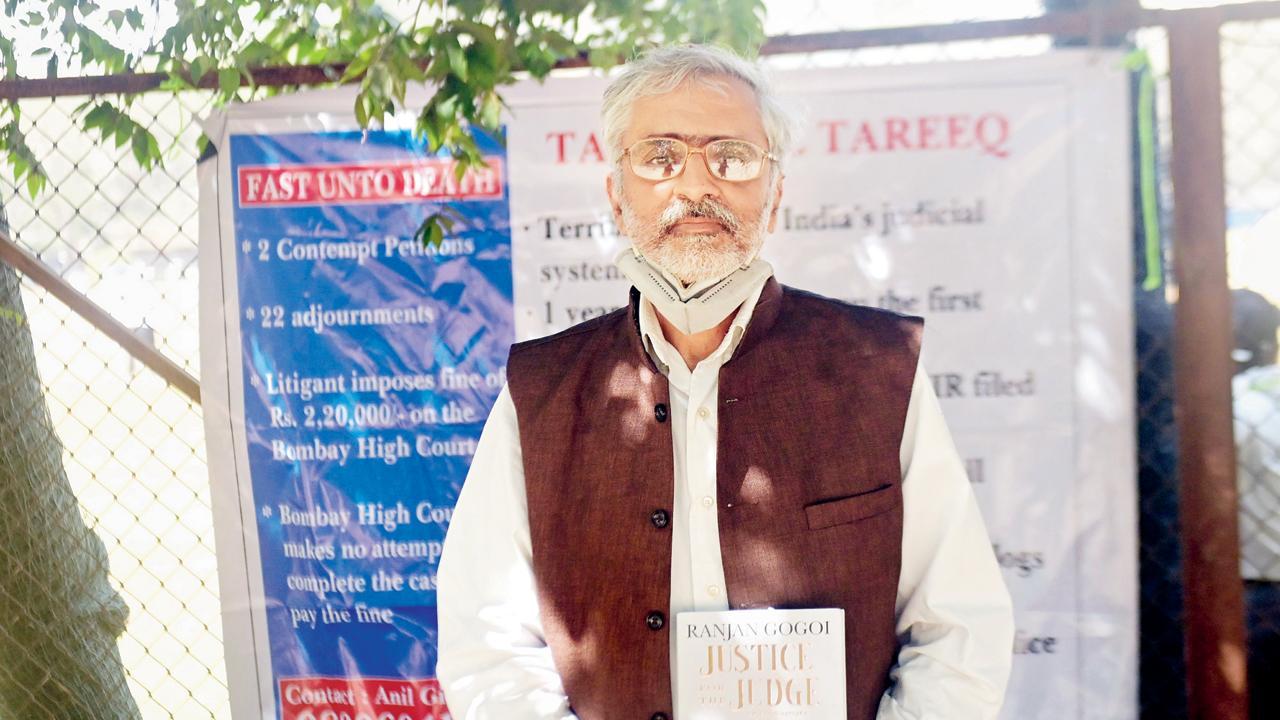

Anil Gidwani at the protest site at Azad Maidan. Pic/Bipin Kokate

Anil Gidwani, 63, has been camping out at the Azad Maidan protest site, opposite the Deutsche Bank, since January 26. The Bandra West resident’s 20-day continuing hunger strike has one aim—to highlight repeated adjournments in the Indian judicial system, the ‘tareekh pe tareekh’ as it is called in layman’s lingo, and hopefully contribute to changing the pattern.

The genesis

Gidwani’s strike stems from a personal place. “I have had a contempt case with reference to a property matter filed against me four years ago. Here there are just two parties, the court and I. Yet, in this instance too, there have been a number of adjournments, and the case is still going on. The idea of a hunger strike began from this point. Yet, I would like people to see the bigger picture. This phenomenon applies to most judicial matters where adjournments and postponements continue for years. At times, the litigant dies waiting for an order, or simply too many years have passed for it to remain relevant. There have been so many reports, research and analyses about our system calling for cases to be heard speedily. Certain cases are now being referred to fast-track courts. Yet, change must be all-encompassing,” said Gidwani.